Is history a fixed chain of facts, or a mosaic of perspectives? When researching technology, some analog narratives often lurk behind our polished "digital age" GPT-summaries. So consider writing itself: earliest notes on birch bark or wax were often personal and ephemeral, not always official chronicles. In medieval Novgorod, archaeologists have uncovered over 1,200 birch‑bark letters (11th–15th c.) – tiny daily notes from merchants, neighbors, even children – offering “the small, personal stories of daily life” that grand histories overlook.

Wax‑coated wooden tablets served as reusable, portable writing surfaces in antiquity and the Middle Ages. One need only picture a Roman cleric etching a ledger on wax (and then smoothing it clean) to grasp how early analog information systems worked. These media show that writing was as much a ritual craft as a record. In such contexts a single quill stroke could carry devotional intent or gossip, blurring the line between sacred ritual and personal note. Such a lineage also does frame writing history not as a singular story, but a layered archive of billions and billions of human hands and lives.

Wax tablets were common for everything from students’ exercises to merchants’ accounts. And likewise, folded birch slips carried messages across town or battlefield. These formats were analogue and recoverable: one can still read the ink on a birch letter or feel the impressions on a wax page. In other words, handwriting history is deeply material. Every ledger, every prayer note, was also an object shaped by craft – from the lead‑point symbols on birch bark to the illuminated codices of monasteries.

The medieval monastic codex illustrates this intimacy. Monks painstakingly arranged text and image on vellum, often embedding cosmic geometry in their page layouts. Florensky even suggested that geometry in icons and manuscripts encodes some other truths, a form of “sacred code” woven into the hand‑written page. In practice, a scribe might add both decoration and devotion to each letter. Often, these handwritten pages contain side‑notes or prayers inserted as if part of the text itself. The act of writing could also, as Rick Rubin suggests, be a ritual: a biblical verse might share a line with a grocery list or a personal lament. This in our opinion blurs faith and daily life. Even when “official” texts were already being produced, the writing process was personal and uneven – a tapestry rather than a behemoth, a monolith.

Scribal Marginalia: Psychogeography and Sacred Geometry

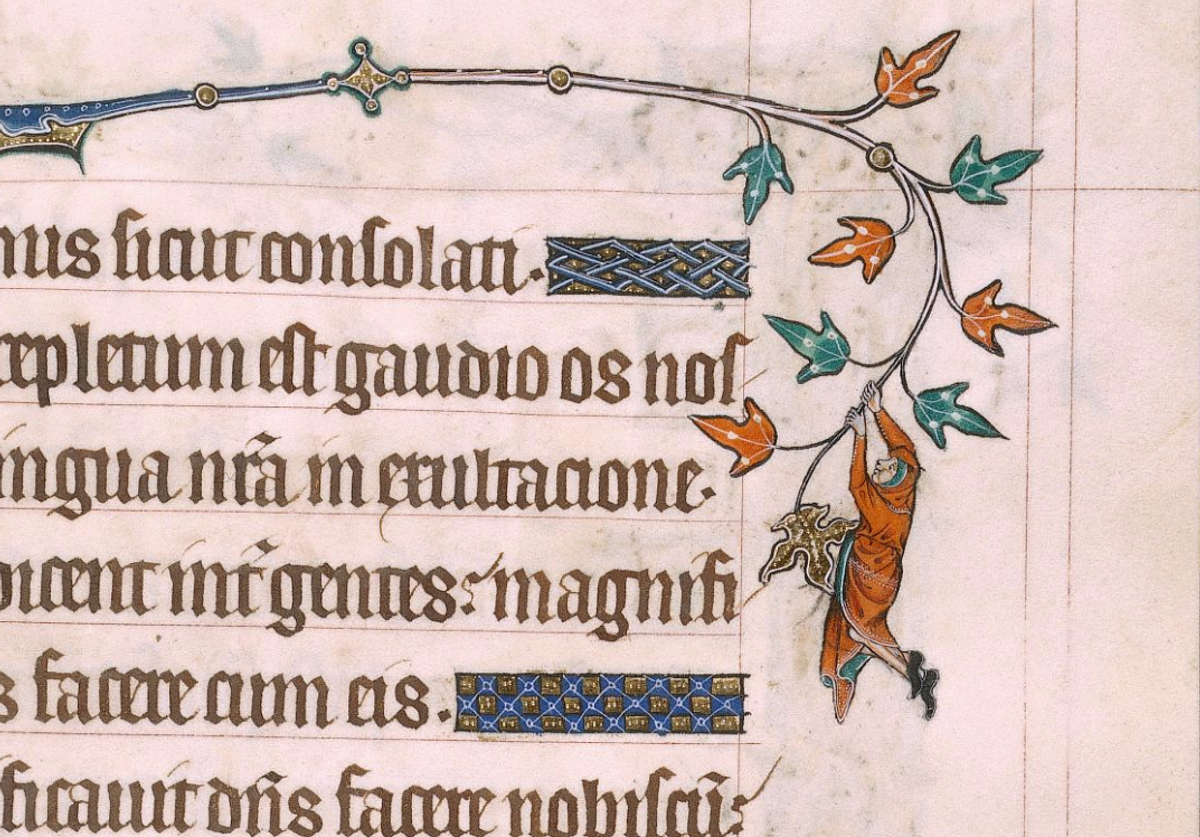

Monastic manuscripts teem with sketches and symbols in their margins. A 13th‑c. Psalter shows a tiny clerk dangling from a vine-letter, and elsewhere knights battle snails or hybrid beasts with human faces. These marginalia are no accident: they encode cultural jokes, mnemonic cues or theological metaphors. As one scholar notes, manuscripts are “time capsules,” and marginalia “provide layers of information” about every person who touched the book

From Manuscripts to Digital Uniformity

With the advent of print and bureaucratic record-keeping, the written word lost much of this analog complexity. The printing press imposed a uniform text – every page looked identical, every letter exact. Local dialects, personal flourishes and marginal secrets were suppressed in favor of standard language and tidy history. In a sense, history itself was being rewritten as one true story. When typewriters and word processors arrived, they further flattened the texture of writing. Typed or pixelated, text became decontextualized data. Some critics argue that these shifts erased the “affordances” of analog media: the tactile feel of ink, the spatial layout of a page, even the intentional use of white space. Where medieval writing let the hand roam freely, digital forms tend to force a single linear narrative. One might even say that official computing history deliberately omitted the quirks of analog: those scribal side-lines, cryptograms, and idiosyncratic notations became “suppressed history.”

Analog Computing and Material Memory

Alternative Technology: The Handwritten Interface Reborn

Today there’s a resurgence of interest in non-digital methods. Pen-and-paper remains popular for creativity and memory: bullet journaling, mind maps, whiteboard sessions. Entrepreneurs and designers are even imagining new analog tools. For example, Outforms – a (hypothetical) modular notebook system – proposes arranging index cards and flowcharts into personal “information circuits,” blending old-school note cards with modern workflows. Intuitively, it suggests the next wave of “alternative technology,” combining the best of analog legibility with digital goals.*

There’s also talk of psychogeographic note-taking: it works like sketching neighborhood maps or room layouts in a lab notebook to jog memory. Meanwhile, some "productivity thinkers" spread tools for logging data with pen in diagrams rather than in apps. These recent 2020s trends echo some long buried strand of tech history. After decades of monolithic computing, people are rediscovering that our interfaces need not all be glass screens. Even large tech firms have introduced physical notebooks and analog brainstorming spaces as antidotes to screen fatigue.

In many ways, current enthusiasts are unearthing suppressed histories. Innovation Hangar spent recent years documenting those tendencies in works like: The Analog Current: Forgotten Pathways in Computing History, this gem traces lost devices and methods of recent past that we found in archives; also Ancient Note-Taking: When Paper Wasn't an Option surveys early media with known methods. Then, an idea of blending art, code and geometry finally finds ist echoes in The Harmonic Interface: Notes from the Periphery, and hand-lettering craftsmanship resurfaces in a brief note on The Leroy Lettering System: Precision Before Pixels. These recent texts (and others that we have done or published) do also suggest to a wider audience that history of technology is not a straight line but a forest of branchings. If we carefully examine hundreds of handwriting and analog tools, we see a lot of things are marginalized for a very concrete reason. Still, each scribble or slide rule chart, every marginal doodle, can also remind us that knowledge has many languages – not just the “official” ones typed in textbooks or coded in offices of Silicon Valley.

So, to finally conclude, whether history is seen as mosaic or monolith, the analog story of writing and computing shows it to be richly plural and varied. If we re able to recover and learn from these obscured paths, analog tech gives us a more... holistic view of technology? The future of innovation may well ride on appreciating old-school interfaces as recoverable, legitimate options and not outdated relics. After all, the past is never just one thing – it is rather a tapestry of voices that is still awaiting to be read aloud.

References on the History of Writing

Medievalists.net – Medieval Daily Life on Birchbark (discusses 11th–15th c. birch-bark letters)

Brewminate – Waxing Poetic: Writing Tablets for Notes and Messages in the Ancient World (overview of wax tablet usage)

Atlas Obscura – “The Strange and Grotesque Doodles in the Margins of Medieval Books” (Johanna Green on marginalia and pen trials)

Further Reading

Here are some more articles on Innovation Hangar to read.

- The Analog Current. Forgotten Pathways in Computing History

- Carbon-14 Analysis Historical Research

- Harmonic Interface Protocols Notes from the Periphery

- Measurements of Composanto

- Field Harmonics in Natural Systems

Ancient Note-Taking: When Paper Wasn't an Option

The Leroy Lettering System: Precision Before Pixels

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий